o

o

o

o

o

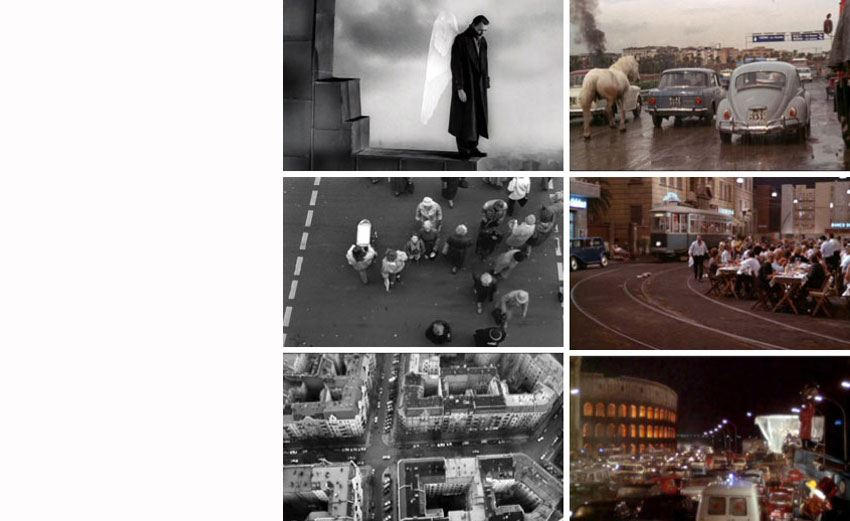

Wim Wenders rodando en Berlín

C’est la raison pour laquelle j’ai tourné en studio: pour que ce soit plus authentique1 (Federico Fellini)

The cinema has created a new way of recognizing the city, due to how the cinematographic language can register the particular space and temporary condition of urban spaces. Cinema can even reinvent the existent city, giving a new vision of some spaces up to the point of distorting the very reality of them.

The improvement of audio-visual techniques is on the basis of this statement. The aerial views, the more and more sophisticated lens playing with the DOF or the development of clear and stable zoom lens are only some examples of how now is possible to approach the city and its inhabitants in another way.

Due to this, it can be said in turn that cinema has changed our way of seeing the city. The perception of the places we inhabit, spaces that make up our daily scenario or, thanks to visionary films, those we dream, are conditioned by a certain personal interpretation of the filmmaker, never belonging to us.

Movies, somehow, have taught us how to look at.

Every city has a precise identity and history, in front of which the director is in the critical condition of a beholder that choose. The look he casts on the urban space and its inhabitants can be intentionally that of a tourist, supposedly objectively distant, or that of someone trying to merge with the breath of the city, becoming inhabitant during the filming. Wim Wenders is clearly stated in this regard, writing that cities do not tell stories, but they can say something about “its history”, and the movies, depending on its open or closed character, can show or hide it2.

The commitment that this director has with the urban spaces in his films is very important. In 1986, he wrote a fundamental text to understand his decision to film Wings of Desire (1987) in Berlin. In this text, Wenders explains what was the specific intention with which he decided to register its urban spaces: A film that might convey something of the history of the city since 1945 (…) it’s the desire of someone who’s been away from Germany for a long time, and who could only ever experience “Germanness” in this one city3.

Finally, he concluded in this text that the only possible inhabitants of that city, at that time divided, could not be others for which the wall does not represent, physically and spiritually, an obstacle: the angels.

Wim Wenders, born in Düsseldorf, feels foreign in Berlin, so he has to think how to record the city. Years later, while preparing his project Lisbon History (1994), also write how the “Fados” of the group Madredeus helped him to overcome the embarrassment he felt for not understanding how the Portuguese city could be part of his history, till the point to include at the end the presence of the band in the story plot. In fact it is known that, during the filming, the music composed specifically for the film by the group was always present4.

Wings of desire (Wim Wenders, 1987)

It seems clear, therefore, that the eye of the filmmaker, except in those cases where it is considered to work in a city or urban environment that belongs to him, is a foreign look constructed of discrete fragments of an urban space, useful for his purposes but which does not belong to him. Paradoxically, this set of scraps will be read by the viewer as a true spatial continuum, a reconstruction of the city in a particular moment of its history that will remain unchanged forever. However, his work does not involve more than a single personal interpretation of something that contains many possible records.

The filmmaker’s look is timeless. Spectators experience the city breathing in the film some time after, inevitably, the gaze of the filmmaker’s record it. The spaces and characters in the screen, linked to a cinematographic fiction, may change or even disappear in time. However, the footage will remain frozen forever without changing.

This is the city shown on the screen, the one our mind rebuilds, without being aware about what we see and what we miss. A city built by non-existent and timeless fragments stored in our memory, and that ceaselessly and fruitlessly we seek in our travels. In the case of missing spaces, or not visited, these images are the only chance of a virtual memory. If later it is possible to experience the real spaces, our perception will struggle to replace these treasured images.

Filmmakers build in us a false memory.

The viewer, filmmaker’s visual accomplice, will rebuild the city through these fragments, assembled in accordance with a particular intention, without questioning the spatial-temporal universe between them. Regardless of the real urban structure -which probably he does not know- and not being aware what is not shown –the off-screen- streets, squares and avenues will compose a fictional but truthful set, subordinated to the needs of the story.

The cinematographic editing is the filmmaker’s great ally in this process, creating with these fragments a new continuous speech able to overlap, or even eliminate, the real architectural space, building a new semantic field necessarily subjugated to the needs of the story. Walker lives the living space of the city as a continuous, interrupted only by brief blinking. As an intentional construction, the film recreates this continuum thanks to these fragments, often recorded with a large temporal and physical distance. But not always: French filmmaker Éric Rohmer clarifies this concept writing about how, unlike Bresson and Resnais films, Lang or Hitchcock movies always achieved an intense spatial continuity5.

Not possible to forget that cinema always plays with two agents: one makes the story; the other one receives it. The conditions and characteristics of both -their culture, visual education, social background, habits and way of living- condition inevitably the perception of the story told and the spaces in which it takes place. A perception, on the other hand, very different to the eventual phenomenological spatial experience, linked to personal sensible experience, which can be taken on these same spaces.

The spectator sitting in front of the screen does not decide the spaces to visit, the way to walk by them and where to direct his gaze: someone has done for him. Instead the walker, even unconsciously, uses the five senses to perceive the space in which he is located. The filmmaker plans a certain strategy to capture the space in front of his eyes, articulating a unique and special way to observe a complex reality that accepts other multiple interpretations. The daily observer, however, experience these same areas with the freedom of that one who can look without thinking.

Watching is at once to know and to decide, two practices closely linked to the human condition.

The gaze of the filmmaker is, therefore, always intentional, a subjective and artificial approach of a reality that always overflows what can be seen on the screen. It is thus a privileged look, as it comes before or after the physical and social reality that the screen finally shows. Arriving before we can speak about architectural utopia; if later, we can consider the images as a silent chronicle of what already exists.

However, the filmmaker decides, of everything he has in front of his eyes, what to frame and what not, and how to do it. And finally, gives us a unique and truthful product, without the possibility of unmasking the artifice that made it possible. Therefore, and focusing the discourse on existing urban spaces, the question arises is how far it is possible an objective record of the city, if there is a filmed city that is not really the city of the filmmaker. How much of report and how much of invention in the images that are shown? Even in the documentary genre, what percentage of reality the filmmaker has decided to frame or skip? How has he directed our gaze, conditioning our reading about a living space that could be read in many different ways?

In an attempt to discern it, attention should be focused in how filmmakers use urban spaces as a frame of their stories.

Generally speaking, movies face the shooting of the city under two different perspectives, frequently interwoven into the same production. The first one uses urban space as a formal and scenographic element; the second, considers it as a neutral container in which the characters of the story are overlapped with the everyday life of the resident society. Thus, in certain movies urban context is merely the backdrop of a story. In others, however, the urban element is determinant and complex, structuring the action over to the point, sometimes, to give it sense.

Under this dual perspective, the relationship between cinema and city can vary significantly depending on the intentions of the director, prioritizing first urban and architectural values, sociological, historical, geographical or just the visual or pictorial ones.

Unless very specific cases, the detailed description of the strictly architectural aspect of the spaces goes to second place. The city and its buildings are used as functional frameworks to develop the actions planned in the script, not diverting attention to the scenery. Robert Bresson has always been a supporter of it:

Que tes fonds (boulevards, places, jardins publics, métropolitain) n’absorbent pas les visages que tu y appliques6.

Wings of desire (Wim Wenders, 1987) / La notte (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961) / Le mépris (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963)

However, they have always existed and will exist directors interested in capturing the very architectural aspects of the city. As an example, we can mention the use in Berlin by Wim Wenders of Scharoun-Wisniewski’s Staatsbibliothek in Wings of Desire, the Villa Malaparte by Adalberto Libera in Capri by Jean-Luc Godard in Le mépris, or the impressive vertical travelling of Milan recorded from the elevator of Gio Ponti’s Gratacello Pirelli, used by Michelangelo Antonioni as background of the credits in his film La notte.

Focusing on those films that give the city some prominence beyond the obvious role of physical support to develop human activities, it is possible to establish a classification based on the interests and varying degrees of objectivity with which the directors decide to record their spaces.

1. The objective cities: Vertov in Saint Petersburg or Ruttmann in Berlin.

Some attempts have been made to build a supposedly objective look over the city, a sort of faux documentary.

The cinema, especially in the beginning, wanted to take advantage of documentary nature of the footage to transfer, from a presumed objectivity, the reality of a city. In these cases, buildings and urban elements become actors together with the set of anonymous citizens walking in the streets. This is certainly one of the lesser degrees of manipulation of the urban scene, but we must never forget that cinema always exerts a deliberate look on a site, so no picture recorded what can be considered objective.

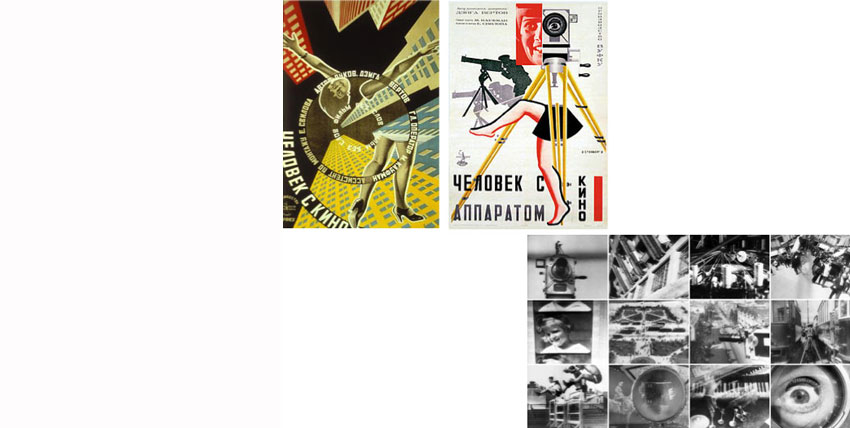

Chelovek s Kino-apparatom (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie camera (s Kino-apparatom Chelovek, 1929) tries to be an everyday portrait of the St. Petersburg’s streets and its inhabitants. Walter Ruttmann took a year to shoot the plans for Berlin: symphony of a great city (Berlin, Die Symphonie der Großstadt, 1927) although the film, organized in five acts, simulates the passage of a single day in the city.

Berlin, Die Symphonie der Großstadt (Walter Ruttmann, 1927)

Both directors states the attempt of a no manipulation of the images recorded -Vertov even speaks about a mechanical eye-, but we must never forget that during the shoot and in the later phase of postproduction, a lot of intentioned variables logically provoke a subjective view of the city.

2. The Recurrent cities: Ozu in Tokyo or La Nouvelle Vague in Paris.

Some filmmakers are so identified with a city that it becomes a necessary texture, present in almost all their films.

Yasujiro Ozu did not always work in Tokyo, but three of his most important productions, the so-called Tokyo Trilogy. However, and regardless of whether some films are shot elsewhere, their actors always seem to be in the same place, a fact for which this town and director are so often associated. Interior and exterior Ozu’s urban spaces are mainly built by independent fragments, static shots of considerable duration -frequently articulated by the so-called pillow-shots8-, very often avoiding to show the movement between them. The city, its structure, is not so interesting itself like its particular scenarios that could belong to Tokyo or any other place9.

Paris nous appartient (Jacques Rivette, 1961), Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Louis malle, 1958), À bout de soufflé (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960) / Yasujiro Ozu: Tokyo Monogatari (1953), Soshun (1956), Tokyo Bonshoku (1957)

Certainly Paris is not only the capital of the Nouvelle Vague, but the city of French cinema produced around 50’ and 60’. Fetish city for many filmmakers, its urban and social structure allowed a host of different approaches, such as Giovanna Grignaffini refers in his study of René Clair, a city able to be divided and mended again infinitely, as a Meccano, changing spatial continuity into temporal one10.

City of memory, thanks to cinema, you think you know it even if you have never been there. And city of desire too, inevitably associated in the collective imagination to romance and love. Just remember in this sense the insistence in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour (1959) of the Japanese protagonist, asking his French lover first if she was born in Paris and later if Nevers was near the French capital. For a foreigner, France is Paris, and this is largely due to cinema.

3. The commented cities: Wenders in Berlin or Fellini in Rome.

Some movies set a particular comment on a city. In them, the filmmakers use the plot to transmit, in a personal way, the pulse of a city and its inhabitants, turning the city into real star of the film.

Wim Wenders was not born in Berlin. As previously mentioned, he chose this city somehow to return to his native country, establishing some reading over a city that intrigues him even if it speaks his own language. The urban angels, who can listen and see without being seen or heard, are the vehicle for deepening spaces and also damaged city dwellers, who speak thousand languages in the manner of a new Babel. The comment that Wenders sets with the city is that of commitment to history.

Wings of desire (Wim Wenders, 1987) / Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972)

Federico Fellini, also not born in Rome, establishes a special tribute to his hometown Rimini in one of his most autobiographical films, Amarcord (1973). In his interesting text Fare un film11 he declares how much in this film as in Rome (1972), he made a special reckoning with himself, with the intention of someone who, after spending some time in a place, decides to empty the apartment and forget all events. An atonement process of the possible experience in one place.

According to statements of the director, this is the spirit in which it is filmed Rome, under the sign of this impatient eviction, intending to exhaust the almost neurotic relationships with the city, neutralizing the emotions and memories of everything lived there. Later, the Italian director sets a more accurate comment about his motivations, explaining that, admitting that he is a terrible traveller, he tried to show that there is no need to travel to capture the unusual, the strange, the unexpected; and then he thought of a Rome scrutinized from the keyhole as a foreigner, a nearby town and distant as another planet12.

4. The visited cities: Coppola in Tokyo or Tanner in Lisbon.

Some filmmakers, fascinated by a distant city, decide to capture with the characteristic perplexity of a stranger, everything that normal people live dayly.

Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003) speak about the story of a meeting between two people lost in a strange city. A place where you do not understand anything, a metropolis immersed in a silence that turns easy the encounter with themselves in the only space that somehow they feel like at home: the hotel. Sofia Coppola, who had lived some time in Tokyo working on fashion and photography, declares that she wanted to recreate in this film the sense of strangeness that this city, from another planet, brings to a European visitor with jet-lag, and how a hotel is the meeting place for all those people with, even unknown, it is possible to establish an ephemeral meeting13.

Lost in translation (Sofía Coppola, 2003) / Dans la ville blanche (Alain Tanner, 1982)

When the Swiss director Alain Tanner received the offer to film a movie in Portugal, he treasured some images, like the boats in the estuary of Tagus River or the stepped streets of old Lisbon. While deciding whether to accept or not to the commission, a TV movie makes him think about how Bruno Ganz could be the protagonist of this rootlessness and scape story. From then on, he starts the preparation and subsequent shooting without a script of Dans la ville blanche (1982), leaving Lisbon memories and present images alloy as something natural, like dictated by the events of the characters, finally confessing that I did not choose Lisbon; Lisbon choose me14.

5. The invented cities: Griffith in Babylon or Scott in L.A.

Some films try to recreate the past of a missing city or the future of an urban space not already existing, and that probably will not exist.

One of the episodes of the film Intolerance (1916) by David W. Griffith is located in the city of Babylon in the year 539 BC. The sets that fictionally reconstructed the mythical city stormed by the troops of Cyrus had a budget very high, about two million dollars of the time. For its design, Griffith was freely inspired on a painting by John Martin entitled The Feast of Belshazzar (1912). The atmosphere that this painting transmits, together with the eclecticism of an architecture that could be called neo-Babylonian, was very efficient to exalt the greatness of a decadent empire.

Intolerance (David W. Griffith, 1916): The feast of Belshazzar (John Martin, 1912), dibujos del decorado de Walter L. Hall e imágenes de la película.

Josep Maria Montaner writes in an article entitled Escena postmoderna y arquitecturas paradójicas15 how in the short period that distance the Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001, A space odyssey (1968) and the two productions of Ridley Scott Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), the perception of a possible future for humanity completely changed. While Kubrick’s film poses a future based on the optimism generated by the confidence in an unstoppable upward trend of human intelligence evolution, in both Ridley Scott films the only future for humanity is the flight, towards the universe in Alien, towards nature in Blade Runner.

Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982): Dibujos del decorado de Syd Mead e imágenes de la película.

The city from which Rick Deckard flees figures to be Los Angeles in 2019, but could be any other, a hybrid synthesis of post-industrial decay and postmodern romanticism. Its crowded rainy streets, always covered in the shadows of the night, not belong to anywhere but are recognized as potential postcards of an imaginary city composed with the most aggressive images of today’s cities.

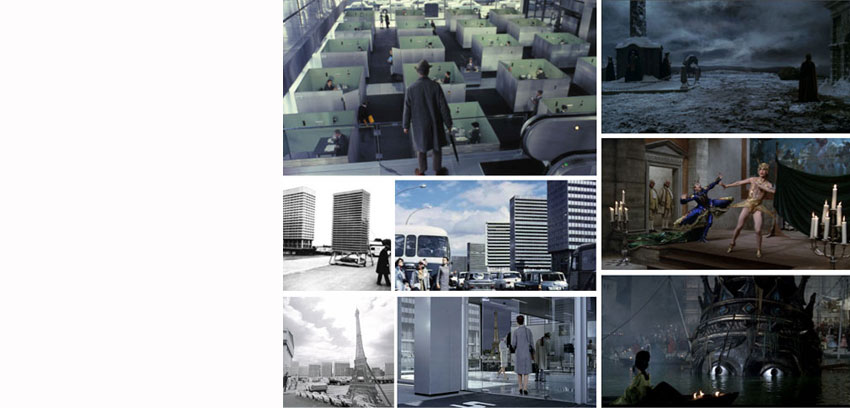

6. The recreated cities: Fellini en Venecia o Tati en París.

Finally, there are those cases in which a studio reconstruction attempts to recreate, with different levels of interpretation, the spaces of a city.

Il Casanova di Federico Fellini (1976)

Fellini plays with the suggestion evoking in studio the city of Venice. The space between the few raised fragments of the scenery is the setting in which the characters can develop their actions: some rigid walls simulating Baroque facades, a few decorated fabrics giving depth to the space and sometimes a reflecting plastic sea recreate the artifice of the town. Our imagination reconstructs what is not seen, but which we known is there.

Fellini plays with the spectator’s memory of Venice, although he has never been there. In an interview with Georges Simenon, Fellini explains how he decided to recreate the city in studio in order to control the perspectives, the colours and specially the light, like a painter on canvas16.

Jacques Tati constructed September 1964 to January 1965 in Joinville-le-Pont, just outside Paris, the city that will support his film Playtime (1967): Tativille. With an area of 8 hectares, the construction of its buildings-wheeled model, mall and stairs required 50.000 m3 of concrete, 4.000 m2 of plastic and 12,000 m2 of glass. The film required 365 days of shooting, divided between October 1964 and September 1967.

Playtime (Jacques Tati, 1967)

In this movie Tati speaks about the monotony of modernity, of a civilization that, in his words, proves the necessity of getting into shop windows17. For some data, the viewer senses that we are in Paris, but the game of Tati in this movie implies that, as the bewildered tourists, we must experience the anxiety of the impersonal modern city. That is why he takes some time to show us something that reveals where we are: the opening of a glass door in an office building shows a reflection of an Eiffel Tower photograph. Now we know that we are in Paris.

Paper made in collaboration with Clara Elena Mejía Vallejo. Presented during the INTER [SECTIONS] sessions. A Conference on Architecture, City and Cinema, developed at the School of Architecture of Oporto from September 11 to 13, 2013.

1. Aldo Tassone, Entretiens avec Federico Fellini. Positif, Paris, 1976, nº 181, pág 6

2. Wim Wenders. The act of seeing. Texte und Gespräche. Frankfurt: Verlag der Autoren, 1992.

3. Wim Wenders, An Attempted Description of an Indescribable Film, 1986. (www.criterion.com)

4. Paul Buck. Lisbon, a Cultural and literary Companion. Lisbon: Signal books, 2002, pág. 134.

5. Licata, Antonella y Elisa Mariani-Travi. La cittá e il cinema. Roma: UNIVERSALE DI ARCHITETTURA, Testo&immagine s.r.l., Segretaria Editoriale, 2000, pág. 3.

6. Bresson, Robert. Notes sur le cinématographe. s.l.: Éditions Gallimard, 1975.

7. Tokyo monogatari (1953), Sôshun (1956) and Tokyo boshoku, (1957).

8. Noël Burch details the concept of pillow-shots in Ozu, long static shots usually without characters used by Japanese filmmaker as a formal solution to solve a wide range of plot situations. [Noël Burch. To the distant obseerver. Form and meaning in the japanese cinnema. London: Scholar Press, 1979]

9. This discontinuity, which characterizes the Japanese director’s distinctive style, has been deeply studied by Jose Manuel Garcia Roig and Carlos Martí Aris in La arquitectura del cine. Barcelona: Fundación Caja de Arquitectos, 2008, pág 147-49.

10. Giovanna Grignaffini. René Clair. Firenze: La Nuova Italia, 1979) (cit. en Licata/Mariani-Travi, 2000, pág. 18.

11. Fare un film. Turín: Einaudi, 1980.

12. Ibíd. Pág. 194-5.

13. Interviewing Sofia Coppola about lost in translation. (August 31th, 2003) [http://greg.org]

14.Interview with Maruja Torres in El País newspaper (June, 15th, 1983)

15. El croquis nº 19. Madrid: Enero 1985, pág 6-10.

16. Dirigido por Federico Fellini, entrevista con Georges Simenon, Diario Pueblo, Madrid, s.f.

17. Du verre, rien que du verre! Nous appartenons à une civilisation qui éprouve le besoin de se mettre en vitrines.

filmarQ.com works only as an educational page, without advertising and without profit or gain, direct or indirect. For questions regarding images or texts property copyrights, please write to contacto@filmarq.com. Thank you very much.